This is the English edition of 'Catnip'.

The German version can be found here →

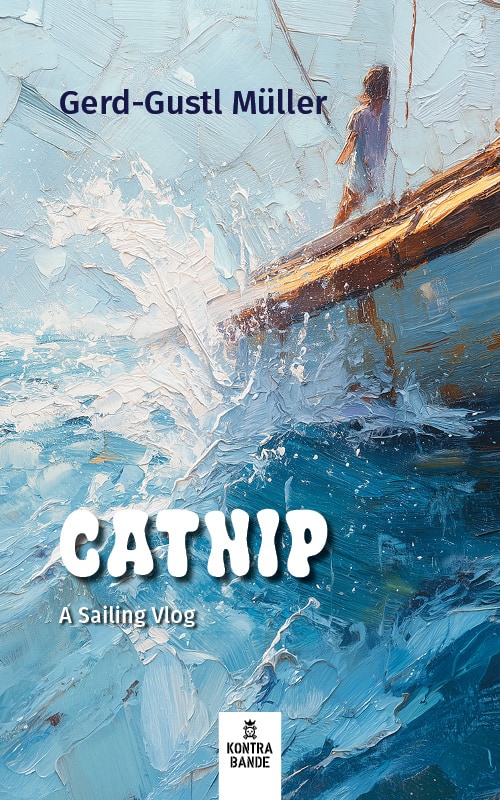

CATNIP

A Sailing Vlog

Gerd-Gustl Müller

A Wharram catamaran that barely floats. A van that barely drives. And three people who no longer want to go anywhere - except away.

Momo doesn't know anything about sailing, but has an old boat. Lia flees from Zoli with her cat, camera and chaos - and Zoli doesn't know whether to look for her or forget her.

Between the lagoons of Huelva, in the crumbling no man's land of self-realisation, their paths meet. Each carries their own story with them: of escape and violence, of failure and silence, of trying to find something that feels like a beginning.

"Catnip" tells of life on board, of vanlife and YouTube, of setting out and diving in - a precise novel about closeness, distance and lack of a plan.

Reading sample 1

All these YouTube sailors, who converted their cheap boats from the 80s to sail over the horizon, had first spent hundreds of hours watching other YouTube sailors rebuild their boats, live on islands, eat lobster, chop coconuts open with a machete on the beach, and drink cold beer with bikini girls.

Not Momo. Moritz Wagner had left his life in Wuppertal behind, had taken off with the old bike he still owned from a North Sea tour with a classmate. This time he had simply ridden away from everything, away, because then everything stayed behind, and south, because it was easier to sleep outside when it was warm. He had never sailed, never wanted to own a boat, had never been interested in vanlife, narrowboats, tiny houses, mobile nomads, or other Gen-Z escape plans because he was too busy messing up his own life and the lives of those around him. That he had stumbled into the sailing scene was pure coincidence, and he still had no clue.

He stood in the open hatch of his ancient catamaran, leaned out and guided the belt sander over the beam that connected the two hulls. He changed the sanding belt, saw that it was the last one and he had to go into town to buy more. He would have to google the Spanish word for sandpaper again.

He took off his safety goggles and wiped the dirty sweat from his nose. He really should have worn a mask. His arms and hands were covered in pale, fine dust. He tried to imagine what his lungs might look like from the inside.

He placed the belt sander on the beam, from where it promptly slipped off and fell onto the hard dirt floor between the hulls, ripping the cable out of the socket in the process.

Momo climbed down the three steps into the port hull. In the forepeak he didn't have enough headroom to stand up straight. He ducked and pulled the dusty sweatshirt over his head. He took a clean shirt from a plastic bag and glanced briefly in the small mirror. His hair had grown long, from dirty-blonde to bleached and shaggy. He went back on deck, pulled the T-shirt on and looked down at himself. A pocket of his cargo shorts was torn. But the shorts were still okay, and he had bought three pairs at Lidl; the other two were still like new. On his left knee, a crusted grey paint residue. Whatever, it's just the hardware store.

He climbed down the ladder leanbing against the stern beam. The catamaran rested on several wooden logs lying directly on the dry earth.

The ground sloped gently to the water, ending just a few meters further down in glistening mud. There stood the large, grey bird again, motionless, its long beak pointing down at the still water. It was always there, stalking slowly on thin legs through the shallow water.

Momo pulled his bicycle out from under the boat. The aluminum frame was scratched, and the luggage rack, all nuts and bolts and chain had turned rust-brown in the salty air. The red roll-top bags hung limply. The starboard bag had a tear from the fall in the Pyrenees.

Starboard bag?

He grinned.

He only had three days left before the owner of the workshop next to where the boat stood would push it into the river.

On the other side of the river arm lay a narrow strip of solid land, grassy and overgrown with low bushes, and behind it, water again. From the deck, he could see far across the marshes, water, then land, then water again, and on the horizon, he recognized the shimmer of the open sea. Beyond it lay Africa.

Reading sample 2

Zoltan Balogh had never owned anything he could have run away from. Starting with the orphanage in Székesfehérvár, through the rotating foster families in Budapest, university, the move to France, and the few jobs he’d held—it was always the same. At some point, he was gone. He never took anything with him, never built anything up.

From orphanage to foster care. Back to the orphanage. Changing schools, interchangeable people, apartments, jobs, girls.

He’d been lucky. He’d known kids who’d ended up in truly messed-up situations—used, harassed, or worse. Boys and girls alike.

He wasn’t bitter. He didn’t know how things could have gone better, and he knew that even real kids in normal families went through wild shit. But in the system, dice were rolled every day—and that never changed.

When Lia started asking him a few weeks ago what he actually wanted from life, and made it pretty clear, more than once, that the YouTube channel was, in fact, her channel, he’d already heard the dice rattling in the cup.

And she wasn’t wrong. It had been her idea. She already had the van and the vanlife channel before they met. The filming always annoyed him anyway. He was hardly ever on camera; people mainly wanted to see Lia—no question. And yes, he hadn’t really contributed much to the van or the expenses. Even though things were often tight. And even though, truth be told, he had enough money.

Most of the time he drove, fixed up the old thing, helped Lia with the tech. He was actually a system administrator. At a computer store on the French Mediterranean coast, he’d seen a girl asking about a SIM card and had stepped in. She wanted to connect a tablet and a computer at the same time, and he’d butted in—surprised at himself—but ended up explaining, choosing, suggesting. He’d followed her back to her van to install a mobile router. That was two years ago.

He helped her with YouTube, managed her online presence, planned the backups, organized and catalogued the massive amounts of files. But she could have done all of it herself. And when she sat there at her MacBook, editing videos or replying to messages, he knew she didn’t really need him.

Then, over the past few days, and after that ugly moment in the Algarve, Lia had gone quiet.

Ugly moment. Misunderstanding. No, he’d understood. He understood exactly.

But after that, Lia—quiet and nice—filming, driving, editing... something had changed.

He’d always found it confusing and difficult to figure out what people really meant when they said things, but now, when Lia spoke to him now, it was clear: she meant nothing. And he couldn’t make sense of it, so for a few days he replied just as politely, with nothing.

Then he went for a shower, and when he came back out, the van was gone. Again.

Even while rummaging through his things and checking what she’d left—ah, his MacBook was still there—he pulled out his phone to call her. But of course, no answer.

He spent the afternoon just waiting next to his stuff by the shower block. Maybe she’d come back.

Once again, he had nothing.

Eventually, he dragged his gear and the bike over to the grass and popped open the pop-up tent. Crawled in, and lying down, checked Facebook, WhatsApp, Insta, Messenger for any fresh sign of Lia. Nothing. Too early—she had only just left.

He lay still on his back.

After an hour, he picked up the phone again and checked. Still nothing, no pings.

He stayed like that for a long time, waiting for the van or for messages, and finally fell asleep.

| Autor | Gerd-Gustl Müller | |

| Titel |

Catnip (en)

A Sailing Vlog |

|

| Erscheinungs- termin |

13. Juli 2025 | |

| Alters- empfehlung |

14+ | |

| Ebook | 978-3-911831-36-9 | 5.99 € |

| Softcover | 978-3-911831-37-6 | 12.95 € |

| Format B x H x D | 127 x 203 x 10 mm | 218 Seiten |